KABUL (SW) – Women artists are among the worst hit by the recent political and economic turmoil in Afghanistan, but their miserable plight has hardly received any attention.

Salam Watandar, in this report, has tried to depict the situation of women artists via exclusive conversations with them. Salam Watandar’s findings from interviews with 21 female artists show that after the recent developments and the imposition of restrictions on women’s work, their business and income has decreased. In this report, 11 female painters, four writers, two poets, two calligraphers, and two others who are active in the fields of writing and calligraphy have been interviewed.

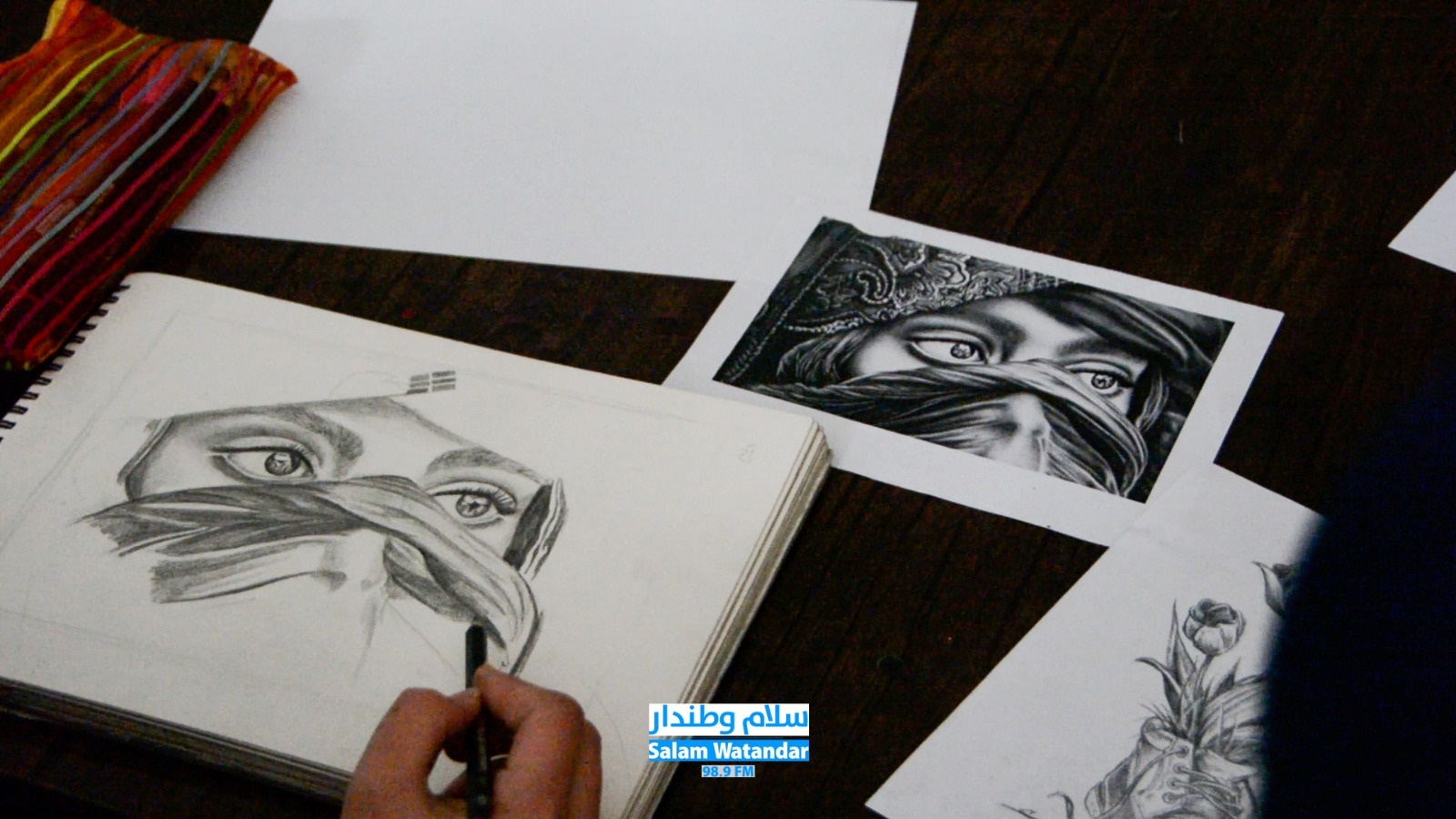

Some 11 female painters who were interviewed in this report say that the art of painting is a way to express thoughts, desires, criticisms and beautify of life and portray their inner grievances and glories, but after the recent developments in the country and with the restrictions imposed on women and painters, they cannot depict faces, living objects, and other critical aspects of fine arts.

Among these women, five have turned to painting after schools and universities were closed for girls, and all of these painters report a decrease or no income. On the other hand, four of them say that their painting schools were closed by the de-facto government and they were not allowed to teach in this department.

Maryam Koshiar, a resident of Kabul who has been painting for two years after dropping out of school, says that she likes to portray the challenges of women, but with the imposed restrictions, she cannot paint critical cases and pictures of the living objects. She added that art and artists have no place in Afghan society and are not supported by the government or people anymore.

Maryam emphasized: “The fields of learning the art of painting are limited, but we still do not get much support from our government. We cannot paint things like faces, a woman’s face because it is against the principles of government. In addition to the fact that I had great enthusiasm and interest in learning the art of painting, but not being busy was another reason.”

Zahra Rezaie has been painting for six years. She says that in comparison to the period of the Republic, very few of her paintings are bought because the activity of painting is faced with limitations such as not painting living objects and about critical issues. She adds: “During the republic, painting of all sorts were allowed. No one had interfered. We used to draw faces, draw nature, draw animals, but now we are confined. We do not have orders anymore. We have no sales. We have no income.”

Lema Naseri, who started painting professionally a year ago, says that her school was closed by the de-facto government and she was unable to continue teaching painting. She stated: “There is a school open, but for the little kids. Before, we used to go to teach and study. We had approximately 40 or 50 female students, but when the intelligence forces came and told the professor that you cannot teach it anymore then the girls were discharged and the school is closed to girls.”

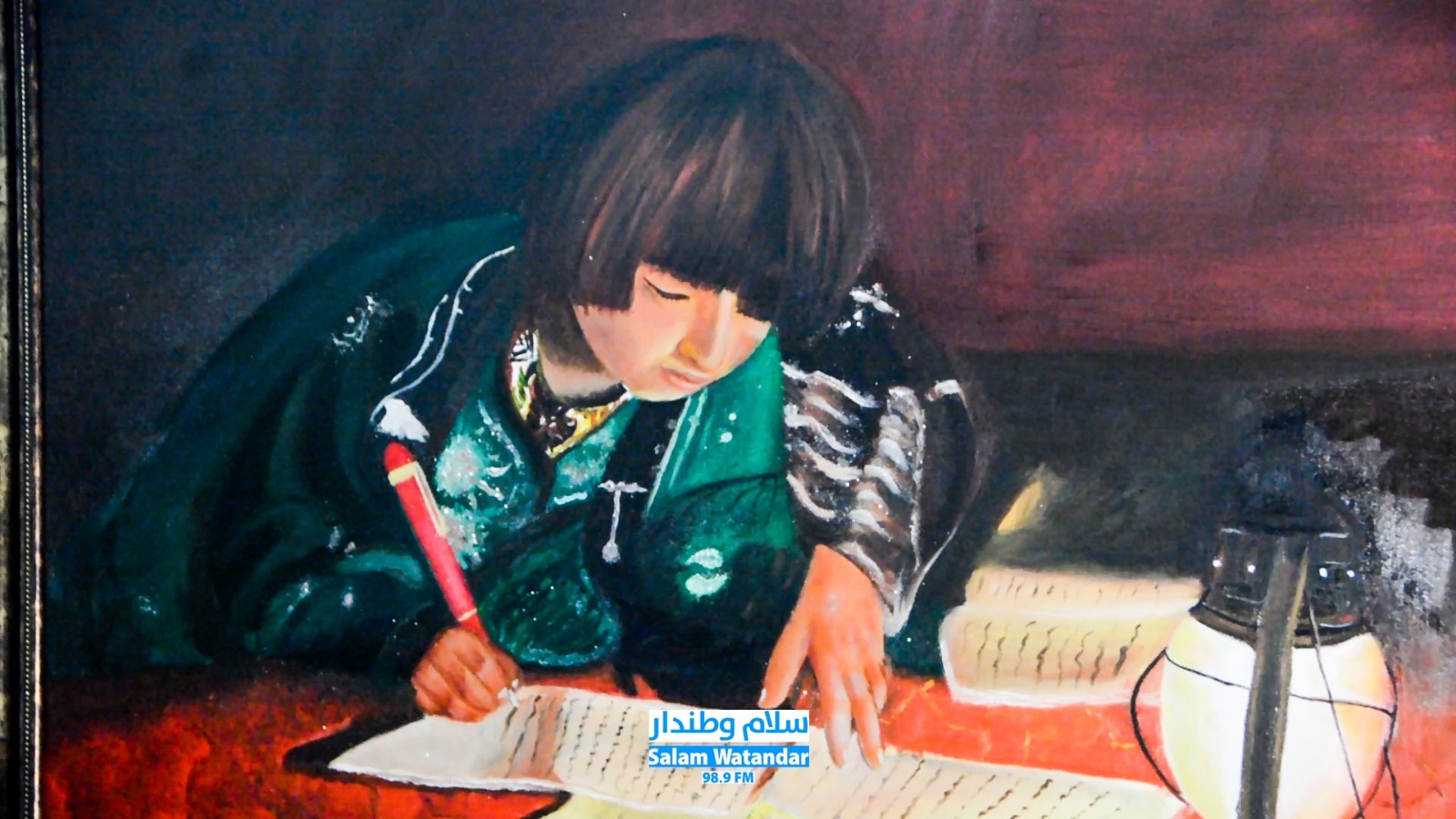

Writing is another way to communicate thoughts and knowledge among people. But, this art for has not immune to the transformation and influence of restrictions. Six women writers, two of whom are also calligraphers and were interviewed in this report, have similar stories about not having the freedom to write, but face self-censorship.

Zarifa Almas, a novelist, painter, calligrapher and senior expert in the Dari language from the literature department of Balkh University, who also has a published work called “Last Night’s Notes”, says that in the past, she earned a good income by writing editorials, but now she has neither income nor can write freely.

She added that in addition to the limitations, she does not have enough financial ability to publish her written works. “Now there are too many restrictions on women. I am a storyteller myself. I had works that I could not publish because of the current government. I have a printed work called Last Night’s Notes. I could no longer publish it. I had a book of poems that I could not be published. It’s not just because of financial ability.”

Meanwhile, Munira, an eighth semester student of law, who considers writing as a way to escape loneliness and silence, says that she cannot publish her writings without censorship. She added that women writers are not supported by the government or any other institution, and this can be the reason for the silence of these women.

“I had a lot of articles,” Munira emphasized. “In addition to being censored, it was not allowed to be published. While it was approved and for now because the universities are closed, I do not see any way to get out of my loneliness. I do not have any income because unlike other countries, writing is not given importance in Afghanistan.

Maryam Mandgar, the author of the book named “Lasting Memories”, also narrates the challenges faced by women writers and the pressure of life on these women, saying that she used to teach the art of writing in one of the schools, but now it is closed.

Two more women poets and four women calligraphers, two of whom are also writers, also have stories to share about work limitations and the lack of opportunities for growth.

Maryam Mirzaei, a woman who writes mostly patriotic, revolutionary and protest poems, and Samira Azimi, a woman who turned to calligraphy after the universities were closed to girls, have stories about the restrictions imposed and the lack of opportunity in the field of poetry and calligraphy.

Maryam Mirzaei said: “I do not think the current conditions are very suitable for women in the field of poetry and culture. There were good programs before; there were good gatherings and there were many programs in the field of poetry. But for now, women are far away from this area.”

Samira Azimi said in this regard: “Compared to other governments, the space for women to work in the art of calligraphy is much confined because the training places or training areas are very few and the time is limited.”

Along with the restrictions on the work and activities of women artists and the closure of a number of art schools, the officials of a number of literary associations also announced ceasing operations.

Farhad Walizada, one of the officials of “Khairkhana Literary Association”, said: “After the republic fell, we could not continue our work with the plans we had before and the freedoms we had before because the presence of young people decreased and the presence of women decreased. In the previous government, the fields of cultural programs were much better.”

Experts in art affairs consider the restrictions imposed on women in various sectors, especially the art sector, as the cause of a deep divide in the society and say that restricting artists can have an irreparable destructive role on the transmission of today’s realities to the next generations.

Zuhal Deldar, who was a teacher at the institute of fine arts and crafts during the previous government, says: “Art has not yet found its place in the society that it should have had. Because it has always been under the influence of the ideology and traditions that have been institutionalized in Afghanistan. The restrictions that are created today in Afghanistan and countries like Afghanistan cause a very deep vacuum in the foundation of that country from the point of view of culture, art, civilization and introducing the country to others.

Khaleda Tahsin, a woman who has been writing poetry in various forms for more than 30 years, said: “Half of the society, the women, when they cannot express their feelings; their affection; their thoughts and ideas; what they feel and what they see outside in the community and they cannot reflect it through poetry, writings, stories and whatever they want to say and write, this itself is considered a huge void and a loss in the society.”

Humaira Qaderi, a contemporary storyteller, said about this: “Actually, what happened in Afghanistan is not just a political fall. What is being experienced in Afghanistan after two years is cultural and social collapse. You will not see the change of society at such a speed anywhere else in the world except Afghanistan. It is practically censorship in parts of the story.”

On the other hand, a number of women’s rights activists say that art is a citizen’s right to express their opinions and criticisms in different ways.

Susan Khaliqyar, a women’s rights activist, says: “It is the right of every member of the society to have the privilege of freedom in the society they live in. It does not matter if they are a taxi drivers or a writers. It does not matter if they are a painters. It does not matter if they are cinematographers. Expressing criticism through humor; through cinema; through books; through poetry; through painting. This is not a negative thing, it is a positive thing and it makes us aware of the gaps in society.”

Despite all this, Atiqullah Azizi, Minister of Culture and Arts of the Ministry of Information and Culture, says that they support artists on the condition that they do not express criticism that is false or defamatory. “Regarding the criticism of poets and poetry, I must say that poetry and speech have an aspect of reform and benefit our nation and country. If the criticism is healthy and does not include defamation and falsehood, we do not have any censorship or obstruction against them.”

This comes as many women artists report about the limitations of their work and the decrease of their income. They said that after the closure of schools and universities for girls in the country, a large number of women artists have turned to art.